Striped maple (Acer pensylvanicum)

A beautiful small flowering tree for shady landscapes, providing food and habitat to birds and pollinators. Native to the forest understory of eastern North America, favoring cool, moist ravines and slopes; requires moisture and full to partial shade in gardens.

Drawing by Landere Naisbitt

Maples are among the easiest trees for people to learn to identify. There are seven maple species in New England, thirteen species throughout North America, and approximately one hundred twenty-five maple species worldwide. Most of New England’s maples are recognizable by the shapes of their leaves and individual species are distinguished by the number and contours of the spaces (sinuses) between the leaf lobes. Leaf color helps identify the maples, as well. Who hasn’t seen the scarlet flare of a red maple (Acer rubrum) in a wetland in late August and thought, ruefully, that summer is waning and autumn is imminent? Maple leaves define autumn in the northern states. In The Tree, Colin Tudge writes, “the maples are the pièce de résistance in the glorious autumn colors of New England, one of the greatest natural shows on earth.”[i]

However, only one of New England’s maples, the striped maple (Acer pensylvanicum), is identifiable by its bark alone. In eastern coastal Maine, striped maples, the second smallest maple in the Northeast, are not overly abundant; and rarely do they reach maturity in the wild, without mishap. But where soils and hydrology suit (cool, moist, forested north-facing slopes of granitic drift) striped maples can grow thirty feet or more, taller than their companion understory trees, the mountain maple (Acer spicatum). Striped maples, even in ideal habitats, have open crowns and are relatively short-lived. They are slender, narrowly branched trees, befitting their preference for shade beneath the forest canopy.

However, only one of New England’s maples, the striped maple (Acer pensylvanicum), is identifiable by its bark alone. In eastern coastal Maine, striped maples, the second smallest maple in the Northeast, are not overly abundant; and rarely do they reach maturity in the wild, without mishap. But where soils and hydrology suit (cool, moist, forested north-facing slopes of granitic drift) striped maples can grow thirty feet or more, taller than their companion understory trees, the mountain maple (Acer spicatum). Striped maples, even in ideal habitats, have open crowns and are relatively short-lived. They are slender, narrowly branched trees, befitting their preference for shade beneath the forest canopy.

Most of the striped maples encountered in Maine have diameters smaller than five or six inches. Many have multiple trunks, evidence of wildlife browsing. Often there are long scars and tattered peelings on the trees’ trunks, signs that bucks have scraped their antlers against the striped maples’ obligingly smooth bark. Two of the other common names for striped maple are apt: moosewood and moose maple.

Drawing by Landere Naisbitt

But young, old, scarred or unscathed, there is one unmistakable characteristic of the striped maple: glabrous, unfurrowed, and striated bark. The stripes are generally white against green but can also be deep green, even black, against reddish-green. Bill Cullina in Native Trees, Shrubs and Vines[ii] describes the stripes as “serpentine” and striped maple is, indeed, one of the so-called snakebark maples, more commonly found in Asia.

Snakebark maples belong to a botanically and geophysically interesting group, or clade, of the widely distributed maple family. The snakebark maples have only one representative in North America, Acer pensylvanicum, while fourteen species are found in Asia, the greatest diversity of all the maples found on that continent.

In the eighteenth century, European botanists who travelled both to eastern North America and to eastern Asia (or studied the herbaria of other botanical explorers) noticed similarities between the flora of these two disparate geographic regions. It was in 1750 that the theory of disjunction was introduced by Jonas P. Halenius (but probably written by his teacher, Carl Linnaeus [1707-1778]).[iii] In 1818 phytogeography and disjunct plants were described in Genera of North American Plants by Thomas Nuttall (1786-1859). Disjunction was often the subject of the correspondence between the American botanist Asa Gray (1810-1885) and Charles Darwin (1809-1882). Gray was the evolutionist’s champion in America. And, significantly, he used fossil evidence[iv] as he sought to reconcile the floristic semblances between two far-flung geographies, bridging time and distance while buttressing the new science of evolution. The phytogeographers are honored in many American plant names, but it was Carl Linnaeus, the author of modern scientific classification, who named Acer pensylvanicum and misspelled the second (species) designation.

Acer pensylvanicum was one of many New World species sent to England by the Philadelphia farmer, naturalist and explorer John Bartram (1699-1777). Bartram wandered from Lake Ontario to Florida, searching for plants to send to an avid British horticultural market. Bartram collected seeds and seedlings, tubers and roots, which were cumbrously (and perilously) transported to his London agent, and fellow Quaker, Peter Collinson (1694-1768). The fraught Atlantic crossings, and delays in recompense (including disruptions and wholesale losses while the French preyed upon English ships and their cargoes during the French and Indian Wars from 1689-1763) nearly bankrupted Bartram. But the popularity of his exported discoveries, the beauty and novelty of American flora eventually transformed British gardening. Since many of Bartram’s specimens, like the striped maple, comprised the Eastern American forest or its understory, a naturalistic style evolved to accommodate the needs of these woodlanders. Acer pensylvanicum is still a prized landscape specimen in British gardens, along with its Asian snakebark cousins.

Acer pensylvanicum was one of many New World species sent to England by the Philadelphia farmer, naturalist and explorer John Bartram (1699-1777). Bartram wandered from Lake Ontario to Florida, searching for plants to send to an avid British horticultural market. Bartram collected seeds and seedlings, tubers and roots, which were cumbrously (and perilously) transported to his London agent, and fellow Quaker, Peter Collinson (1694-1768). The fraught Atlantic crossings, and delays in recompense (including disruptions and wholesale losses while the French preyed upon English ships and their cargoes during the French and Indian Wars from 1689-1763) nearly bankrupted Bartram. But the popularity of his exported discoveries, the beauty and novelty of American flora eventually transformed British gardening. Since many of Bartram’s specimens, like the striped maple, comprised the Eastern American forest or its understory, a naturalistic style evolved to accommodate the needs of these woodlanders. Acer pensylvanicum is still a prized landscape specimen in British gardens, along with its Asian snakebark cousins.

At any time of year the striped maple has a distinctive beauty. The tree’s colors are varied and arresting. In winter, bright crimson buds sit like finials on blood-red twigs. The younger bark on striped maples has white or green squiggles of varying lengths. Trees can also be red with black or dark green stripes; seedlings can be unstriped red, burgundy, deep green or black. Stripes become more conspicuous when trunk diameters reach a few inches. Mature striped maples may have a greyish bark, “warty” according to Sibley’s Guide to Trees,[v] with striping confined to younger branches and limbs. The smooth bark can photosynthesize in winter.

The leaves of striped maples are the largest of any of the maple family, seven inches across at the base, nearly twice the size of the leaves of sugar maples. The leaves are long-stalked, palmately compound with three to five finely-toothed lobes. The striped maple’s distinctive leaf shape accounts for another of its common names, goose-foot maple. The summer green is one of the forest’s purest colors; fall color is clear yellow, indicating an absence of the chemical anthocyanin that transforms most other maple leaves into a festival of reds and oranges.

Drawing by Landere Naisbitt

In spring when striped maples are nearly in full leaf, bright yellow bell-shaped flowers appear on long, pendulous racemes. The flower stalks of mountain maples also materialize after the leaves have matured, but these flower clusters are upright, held above the tiers of foliage. Comparison between these species is easy because the two are often forest companions, preferring the same habitat of cool, moist, acidic woods.

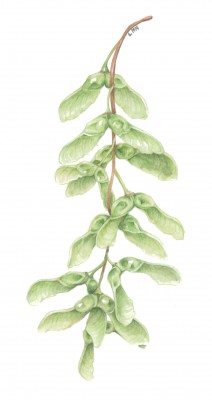

Striped maple fruits, called samaras, are ripe in late summer or early fall. Chains of these winged seeds dangle fetchingly beneath the outsized leaves. Most trees of the temperate forest depend upon wind for pollination, though insects may still visit for nectar or pollen. Striped maples are predominantly male trees, that is, their flowers are male. But the species exhibits sexual dimorphism or plasticity. If changes occur in the canopy and new conditions seem favorable, trees can alter sex, bearing female flowers in a single generation.[vi] Sex choice or gender diphasy is also found in Jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum) another forest denizen listed among the American-Asian disjuncts.

Drawing by Landere Naisbitt

In the wild, striped maples suffer few pathogens or diseases perhaps because they are so habitat-specific and will not grow where stresses like strong sunlight or dry soil would create vulnerabilities. Even senescent, fallen or dead striped maples have few saprophytes; the smooth bark discourages the attachment of fungi and mosses until there is advanced decay of the trunk. Predation by deer and moose cause the trees their greatest injuries. Wildlife, including rodents and grouse, eat striped maple seeds. Maples sustain a large number of arboreal lepidoptera (moths and butterflies).[vii]

Striped maples are singularly beautiful trees. They are among the most shade tolerant of all trees in the Northeast. They are naturally found in a rough triangle from New Brunswick to southern Ontario, down the Appalachians, dwindling in numbers through the mountains of North Carolina to the highest elevations of northern Georgia. Striped maple seeds germinate fairly well, though seed-collection requires shrewd competition with birds and squirrels.

The habitat requirements of striped maple trees are more limiting than other maples. Careful siting makes these beautiful trees garden-worthy in shady locations with cool moist soils; and elsewhere, striped maples are worth searching for, to admire in their forest homes.

By Pamela Johnson

[i] Tudge, Colin. 2005. The Tree. New York: Three Rivers Press. see Tudge’s analysis of the chemistry of autumnal leaf change, pp. 357-58.

[ii] Cullina, William. 2002. Native Trees, Shrubs, and Vines. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

[iii] Boufford, D.E. and S.A. Spongberg. 1983. Eastern Asian-Eastern North American Phytogeographical Relationships- A History From the Time of Linnaeus to the Twentieth Century. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 70: 423-439.

[iv] Yih, David. 2012. Land Bridge Travelers of the Tertiary: The Eastern Asian-Eastern North American Floristic Disjunction. Arnoldia 69/3. pp.14-23.

[v] Sibley, David Allen. 2009. The Sibley Guide to Trees. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

[vi] Schlissman, Mark A. 1988. Gender Diphasy (“Sex Choice”). Plant Reproductive Ecology. J. Lovett-Doust and Lesley L. Doust, eds. New York: Oxford University Press.

[vii] Tallamy, Douglas W. 2007. Bringing Nature Home. Portland: Timber Press.